Why I wrote this book

I wrote this book after someone asked me why I hadn't written one. I had spent years advising organisations on buying and selling services, but also teaching on the topic at Carnegie Mellon University. But the impetus to write the book came from being dissatisfied with a dominant narrative. Services were being glorified as the superior way of creating value. Books, blogs and speeches were talking about a future in which everything will be a service. They pointed to wealthy economies with more than 70% of GDP from services. The gig economy was gung ho and the sharing economy was going to tell hotels and taxi companies to shove off!

But I saw services in a less flattering light. Yes, they're a key form of production and societies cannot exist without them. But too many were failing or falling short of expectations, and for flimsier reasons than manufactured goods. All problems were attributed to not putting the user at the centre of a design process. Human-centred design became a hammer, and every service a nail. Not much was written or said about the deeper, structural problems; congenital defects due to humans being human and services being services. What forces airlines to strip away basic comforts and conveniences and sell them back to passengers as options? Why was Uber not going to make money from ride-sharing despite the nice UI/UX of its app? Why do people drive and not simply show up at a bus stop?

That's why I wrote the book.

Why you should read it

You should read it if you're interested in a deeper understanding of what services are, why they even exist, and why they disappoint as they do. You should read it if you are working on a policy or strategy that is forcing you to question the fundamentals of a business or a government. You may have to restructure the very risks that make the service even possible. Or, you have the unenviable position of making a service more sustainable but the odds are against you. Although the subtitle of the book mentions strategy and design, this book is not just for designers and strategists. It's for anyone interested in a new way of looking at services, as arrangements and agreements. Arrangements between things and agreements between the people behind those things.

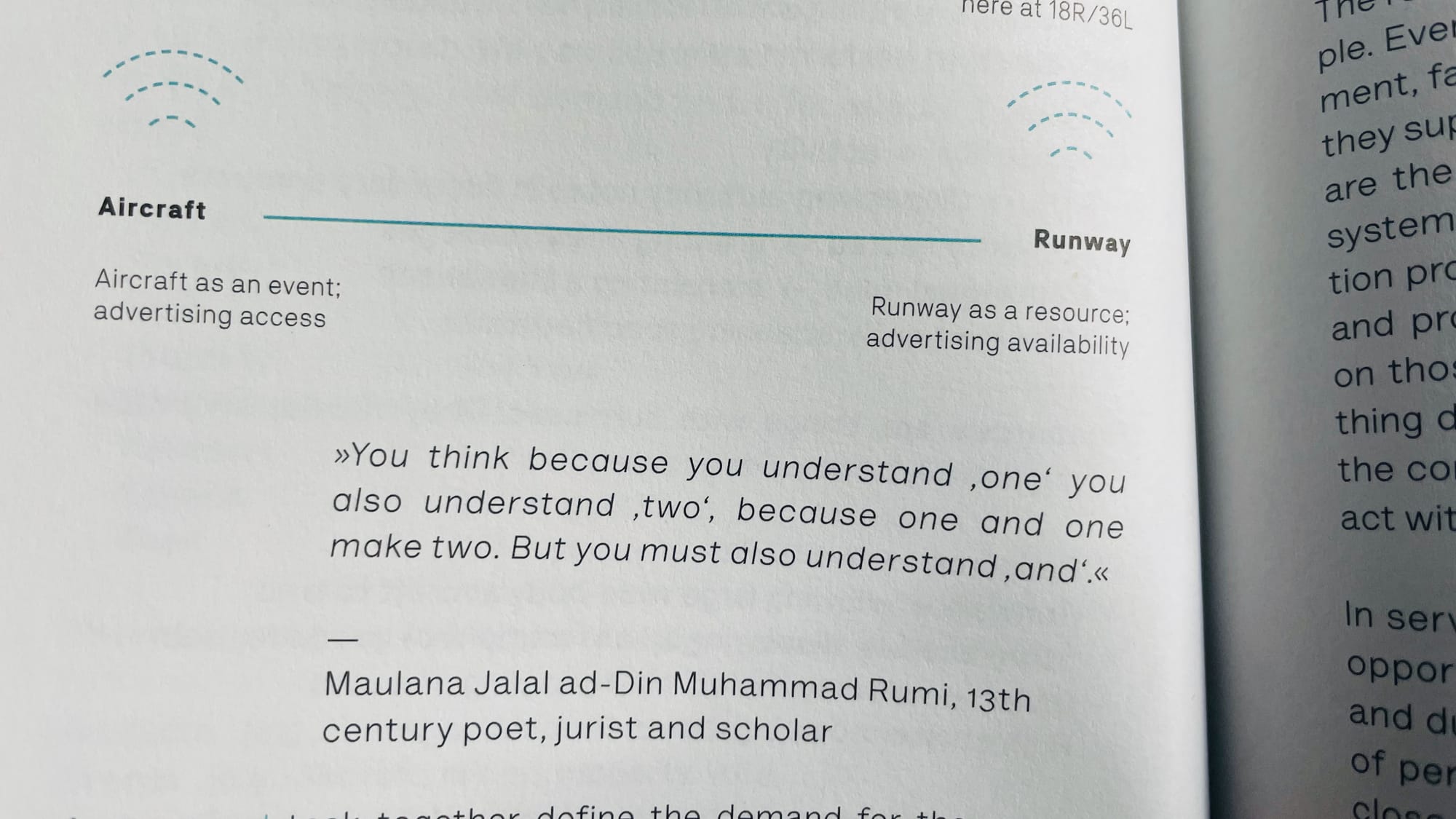

The book has several anecdotes and examples and invokes well-known principles of design, engineering, and economics. But it also employs abstract thinking because that's how we reach new levels of understanding – our minds jumping on a trampoline higher and higher to see over a mental block. The book introduces a markup language that is useful for analysis and research, but also for constructing arguments and composing narratives. It also introduces a set of genetic traits or patterns you can detect in all kinds of services. Thus, you can see the similarities and differences between hotel beds and hospital beds. You see why a technology that originated in healthcare was easy to adopt at airports to reduce delays. You can see how, from the Piggly Wiggly to the Amazon Go, grocery stores are about private stocks on public shelves.

You should buy this book, whether you read it or not, because it is beautiful – designed in Germany and printed in the Netherlands on gorgeous paper and ink. That's also why we did not publish a Kindle version. But if you do read it and like it, then do not hesitate to send me a heart-warming note, like this one I received from Australia:

It's like you write just for me. I'm a dyslexic service designer and sometimes feel like I can only see complexity - it's my happy place.

Writing a book is not easy. It consumes a part of you that may never get replenished. Not every author gets rich or famous. But receiving such notes of appreciation makes it worthwhile. If there is a book in you, then write it. It is a life changing experience and way to add to the world. And, since I have never before written about my book, I might as well share with you a few key moments from my own experience.

The process

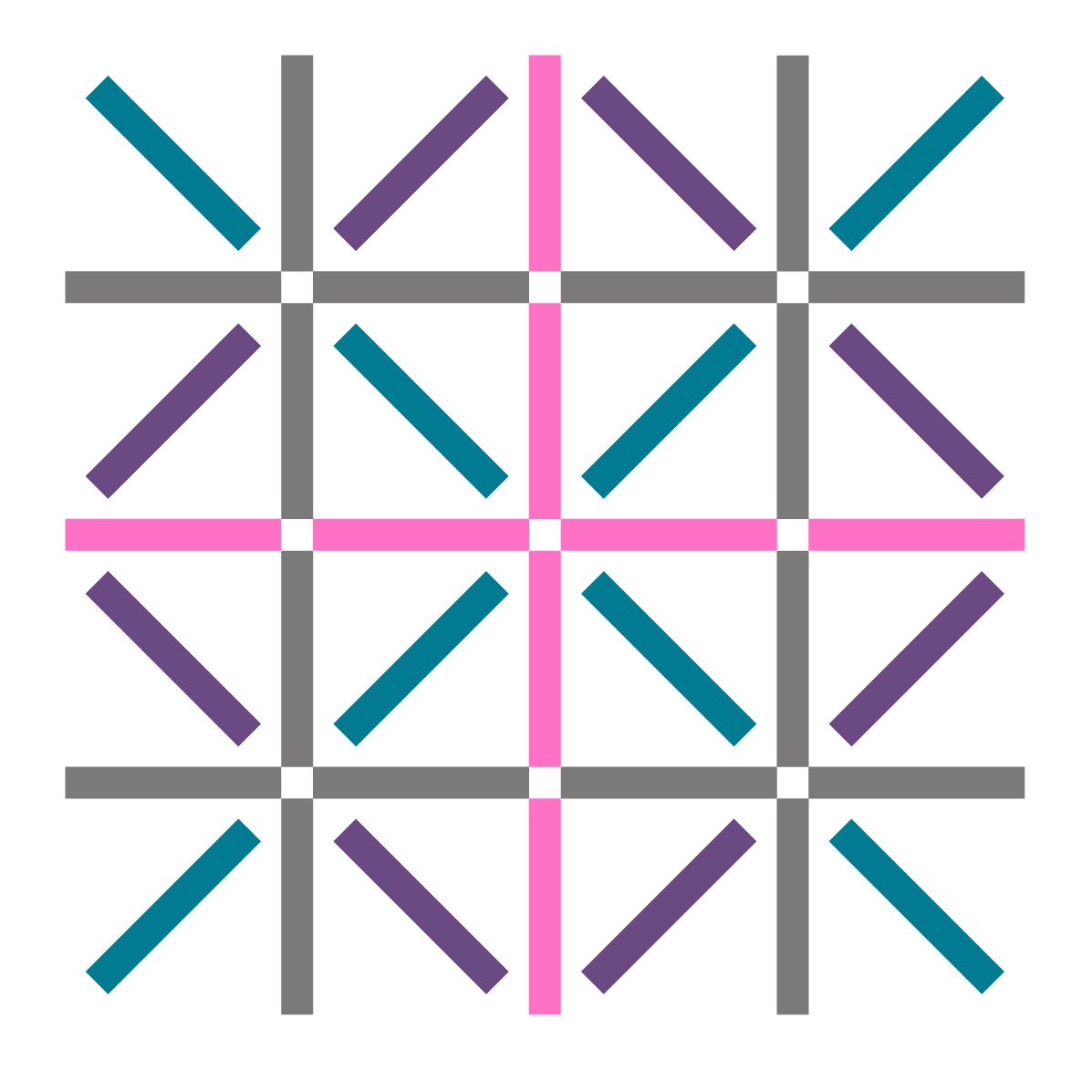

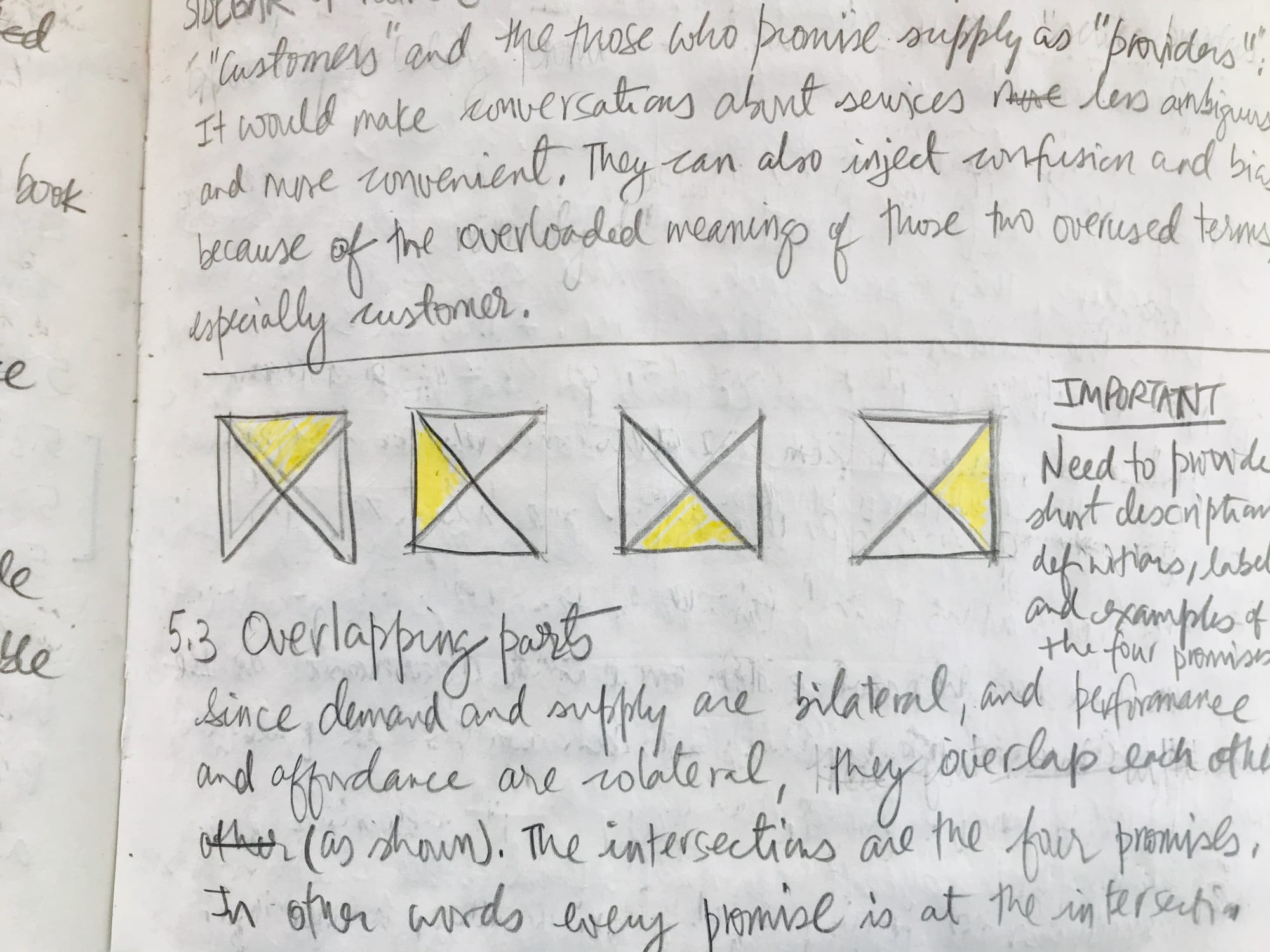

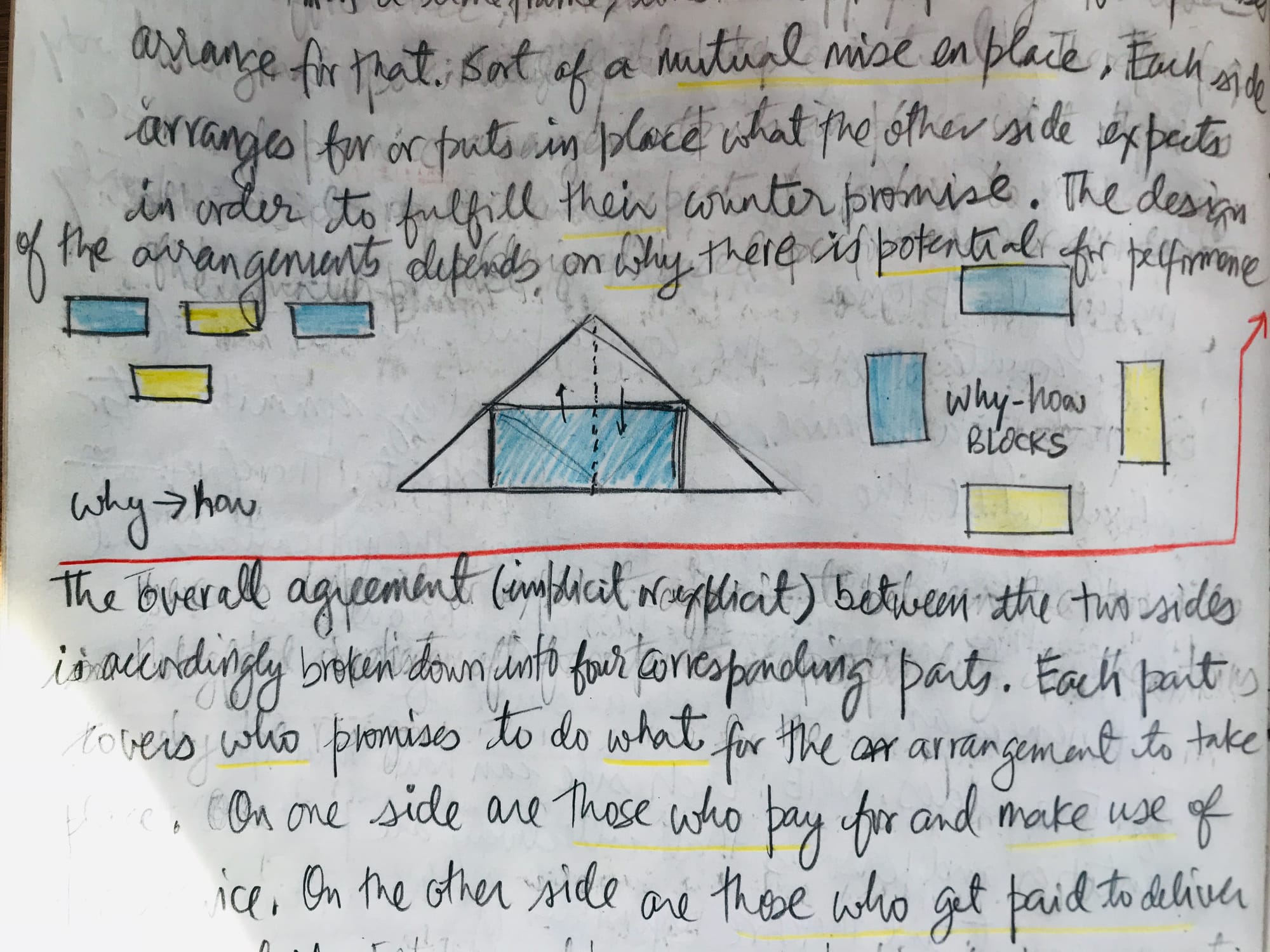

It took roughly two years, from the time I received an advance payment from the publisher, to the day the printer received the file. I had a lot of notes and sketches and a rough idea on how to approach the book. The advice I got from my publisher, Bionda Das, was to relax, enjoy the process, and write in my own authentic style. So I went down the path, starting with pencil and paper to write more fluidly at first. In my experience, pencil and crayon were helpful in creating the material necessary to explain key and fundamental concepts, such as the idea of four overlapping promises in every kind of service.

A key concept in my book is that of a promise. Promises are the structural units of contracts and services, which are the building blocks of economies and societies. Taking the common, dictionary definitions of promises and turning them into an architectural concept was a key task for me. I still remember the joy I felt when the drawings started to crystallise the concept. I was in Baltimore, Maryland, holed up in an Airbnb, hosted by two architects.

Needless to say, having a place where you can sit for hours and write day after day is so very important. Away from everything; just you and your paraphernalia. The place I rented in Baltimore for a month, had a simple desk and chair, and good daylight. That mattered a lot.

After the first draft was done, I moved to Stockholm for a month where I was hosted by David Nyman and colleagues at a boutique consulting firm. David and company believed in my work and provided me with financial support that was very helpful at that time, because I had taken a sabbatical from my own consulting work. Apart from covering my living and travel expenses, they also paid for the graphic design and the special paper the designers picked for printing. I don't think I could have written the book without their support.

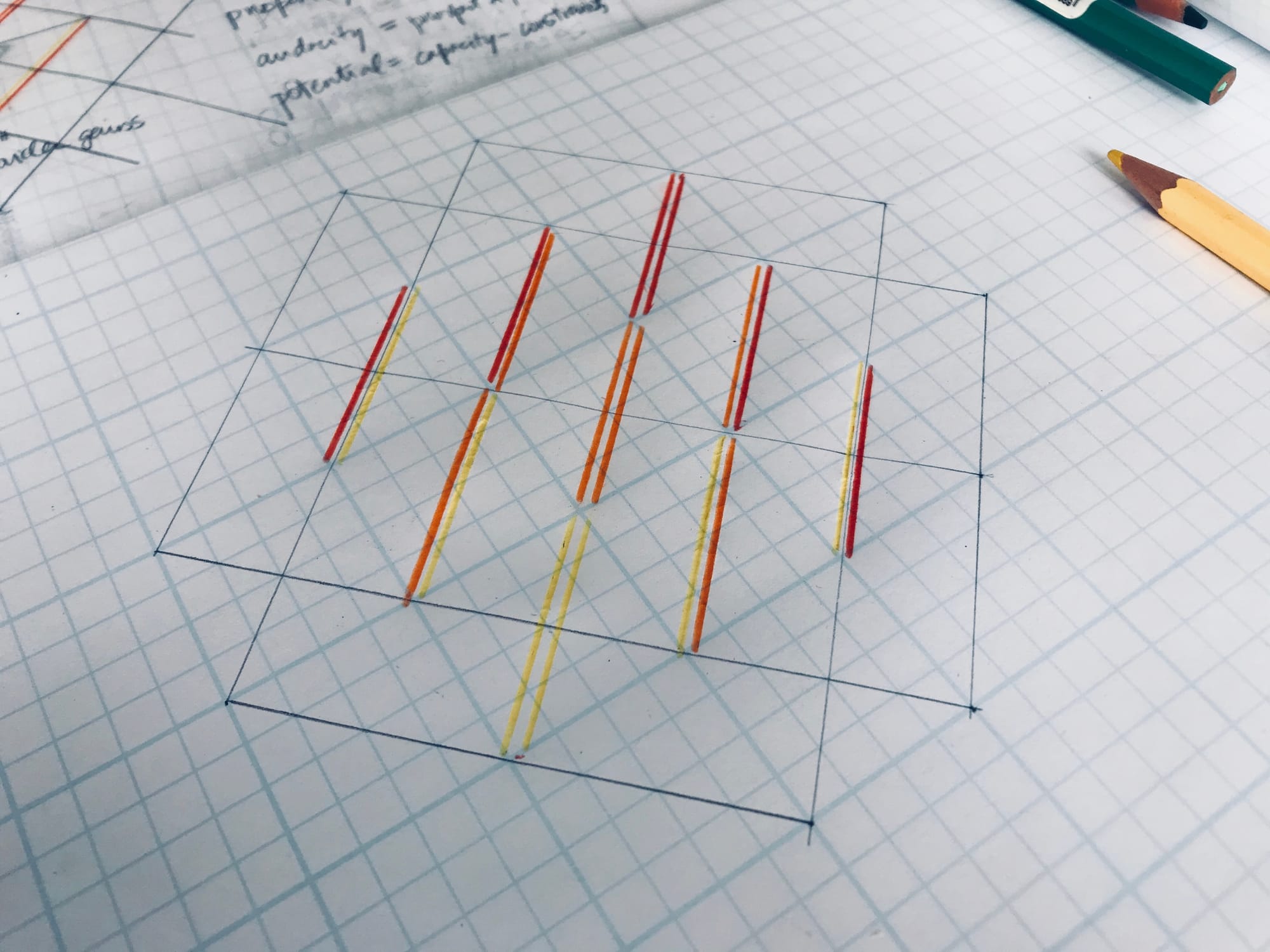

In Stockholm, I developed a diagram that explains the tensions and trade-offs between customers and service providers. I initially called the diagram a 'playing field' but then renamed it 'empathy graph'. It has three regions – optimal, suboptimal and suck – based on whether the value each side gets from the service is Not OK, OK or Great. Using this graph you can understand or explain strategies commonly used by startups and incumbents, such as the hook and the swap. Or, explain success and failure using the upward spiral and downward spiral. The concept applies to dynamic systems in general; the imbalances between the capacities and loads of systems and wasted potential due to faulty design.

Paper, pencils and crayons are of course not enough. Before moving to Word, I used Ulysses as my text editor. It is a beautiful piece of software designed keeping in mind authors and journalists. I highly recommend it. I originally bought it as standalone software. But for the past few years I've been paying for an annual subscription, ever since it became, wait for it, available only as-a-service. There was another thing that became unexpectedly useful in inspiring an idea for the book. Cuboro is a marble run system designed for children to play and learn architectural patterns. It is expensive but because the wooden blocks are beautifully machined out of birch. One mention of it and David went and bought a whole set, including a binder full of designs.

Cuboro was useful in developing explanations for how services can be flexible and modular, with blocks of promises arranged in sequences. Each block has its own performance, affordance, outcome and experience. A block can be a service on its own, available through a third-party contract or API. We can rearrange the blocks into sequences that produce the desired effect or end result at lower costs and lower the chances of failure. It was exciting to come up with better explanations of well known problems. Writing the book was a good experience that way. Every now and then, I feel the urge to do it again. Although I still can't get used to signing copies. I feel embarrassed and shy. Well, that's all I wanted to share about my book. I hope you're curious enough now to buy it. You can read an excerpt here, here and here. There is also an interview I gave on the book. Every now and then I also teach a course that uses material from the book. The latest one is about industrial analogy and abstraction; techniques I feature in the book.