Services are the soft infrastructures of societies. Everything runs on them. Mining, manufacturing, and agriculture. Industry, and government. If societies could power down to a low-energy standby mode, there would still be services running in the background; economies emitting carbon at a basal metabolic rate. Services also boost economic growth. Therefore, we cannot attain net zero nirvana without making all kinds of services more sustainable. But that will not be easy, because services are more than just activities or processes, as is commonly understood. They are joint ventures of risk; risks people want to take, not avoid. Like with cholesterol, there are 'good risks' and 'bad risks'. Good risks are shareable. Attempts to reduce costs, or carbon, shouldn't let good risks fall below a threshold, otherwise the very concept of a service will collapse. We could say we can live without some services; let them fail. But some services are like keystone species in ecosystems and, the way our systems are hyperlinked, failures may be hard to isolate. What we could do instead, is to reduce the unshareable risks that are bad because they create unnecessary costs – costs that customers and service providers impose on each other through terms and conditions. That way, we create room for the necessary costs of making a service sustainable, and have the two sides supporting each other, instead of stressing each other out.

Introduction

Countries around the world are confronted with a spending-saving problem. Imagine there is a global carbon budget i.e. the total amount of "carbon" a country can spend without worsening global warming or stalling its economy. Then every country has to spend enough on its present populations, while saving enough for future generations. But, many countries may already be running on a budget deficit, whereas, they need to have surpluses to accommodate additional prosperity and growth. To even maintain current standards of living (let alone raise them), they really have to remove carbon from just about everything. Removing it in agriculture, mining, and manufacturing is one thing. Removing it from services is harder for a reason.

Demand and supply are more tightly coupled in services; we can delineate but not separate production from consumption. But what truly distinguishes services is that even the simplest service is a 'joint venture' between someone assuming risk and someone avoiding it. Someone is doing something so others don't have to. Someone owns something so others don't have to. That means, services at their core, are concepts of enterprising risk. That is not to be confused with the risk we associate with uncertainty and doubt. Any attempt to reduce costs should be mindful of that distinction. As should any attempt to reduce carbon. Furthermore, it is difficult to make changes to the enterprise, without the commitment and support from all sides.

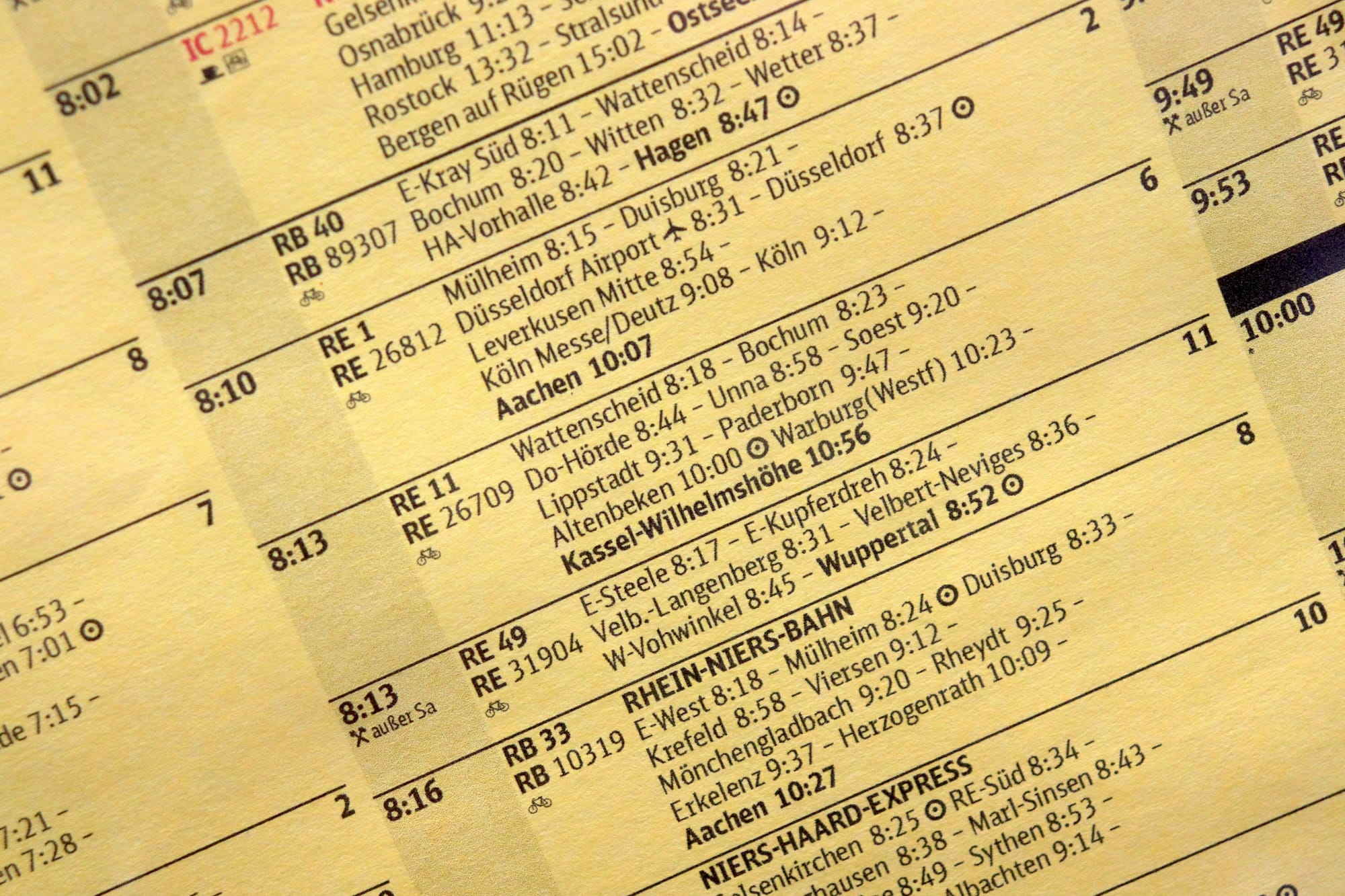

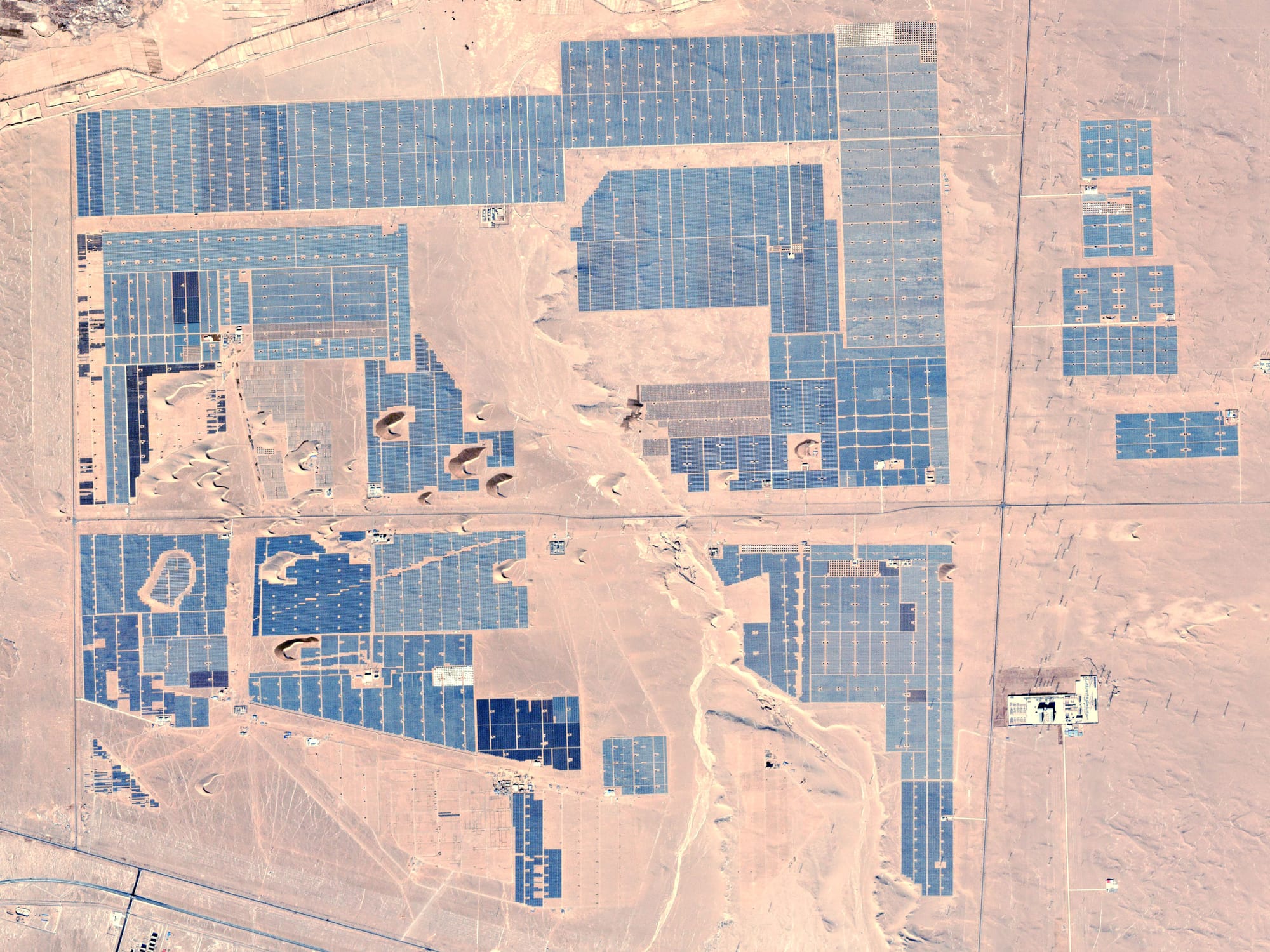

Businesses around the world are taking steps to make their services more sustainable, but the journey can be stressful. Green technologies and materials are necessary but not sufficient to achieve net zero. Not by a long shot. For example, airlines receive a lot of attention for the sheer volume of their emissions. So they are investing in more efficient engines, airframes, and sustainable aviation fuel (SAF). But transitioning away from fossil fuels will take time and not without economic stress if financial and non-financial buffers are thin. Air New Zealand recently became the first major airline to abandon its 2030 climate goal citing challenges with fleet upgrades and the SAF costs. Airports aren't having an easy time either. Their fees are capped and their capacities are limited. Like cinemas staying afloat on popcorn and soda, many airports rely on retail and real estate revenues to be financially viable.

Commercial aviation is just one industry. There are so many different types of services. The industry around each type will have its own reckoning based on the nature of the service it provides. Every industry has not only its carbon intensity but also colour. We must understand the various colours of carbon to understand why each industry will have its own struggle. In doing so, let's follow the advice of Kenya Hara:

“To understand something is not to be able to define it or describe it. Instead, taking something that we think we already know and making it unknown thrills us afresh with its reality and deepens our understanding of it.”

Let's revisit our understanding of what services are, why they even exist, how they encourage us to take risks and fulfil our potentials, and why making them more sustainable can be harder without the support of customers and suppliers.

1 Soft infrastructures

Not a day goes by in the lives of individuals and organisations, without relying on services. Societies around the world evolved, and crossed a threshold at some point in history, to become heavily dependent on services. We have made an irreversible shift not unlike the one we made thousands of years ago, from hunting and gathering to agriculture. There is no going back to living without services. We use more services in a single day than our ancestors did in a lifetime. Life feels normal with services. Indeed, after any major incident or disaster, normalcy is said to be restored when services resume operations. When electricity is back on, trains are running again, and payments are processed. The forces that restore normalcy are also services.

"Basic services"

Services satisfy our basic needs. They provide energy, food, and transportation; education, healthcare, and entertainment; security, justice, and rights; passports, licenses, and permits. We expect such services to be available to all regardless of income or status, at affordable prices if not free of charge. Some are so essential to dignity and freedom that we prefer governments to provide them. As taxpayers, we also provide crucial funding for special bundles of services, such as defence, foreign affairs, and national intelligence, even though we don’t directly use them in the conventional sense. That's why now and then we argue about how much to spend on them.

"Norms and impositions"

You can go anywhere in the world and find a universal set of services. Too many air-conditioners break in some places, while in others boilers, paths need to be cleared of snow. But in both cases, skilled technicians provide maintenance and repair services. What changes from one place to another are the services imposed by rules, regulations, and culture. For example, some countries expect you to carry all kinds of insurance because of the greater likelihood to be sued in court for damages. In some countries, even health needs to be insured. In some societies, people rent tuxedos before important occasions while in others they pay astrologers to read horoscopes and pick auspicious dates. In some societies there are grooming salons and hotels for pets while in others even rescue shelters for stray animals might be rare to find. Lastly, there are variations in volume. It is easier to license, borrow, or rent things in some countries than in others, partly because of the overall effectiveness of law enforcement in enforcing property rights.

"Per capita"

Societies need services for every additional member. Even before we are born, our parents receive obstetric care, our health is monitored, and pictures are taken in ultrasound. Upon arrival into safe hands, we demand documentation such as hospital records, birth certificates, social security cards, and insurance, even as we transfer from obstetrics to paediatric care. From that point onwards, now and then, and for the rest of our lives, we keep asking for documents, such as school certificates, college degrees, passports, driving licenses, and marriage certificates. We don't benefit from our death certificates or obituaries. But those who we leave behind, they do. That way, as »natural persons«, we create demand for services, from the time we are born, till after we die.

"Per capital"

The same is true when »legal persons« are born, whether as businesses, foundations, political campaigns, communities, charities, or trusts. They are born with the propensity for services – as they go about registering with authorities, raising capital, and advertising their offerings. More services are needed further on and in different phases of the life of a corporation, provided by other businesses and governments. Some needs are predictable and periodic, as with the maintenance of buildings or equipment, payroll processing, and office rentals. Some needs are occasional or extraordinary, such as with raising financial capital, market research, and disaster recovery. Every up and down, twist and turn, expansion or contraction, creates demand for services. Organisations need services even as they cease to exist after acquisitions, bankruptcies, and dissolutions.

2 Propensities and audacities

Our propensity for services exists because we humans are restless, relentless, and enterprising by nature. We are always up to something. And, when faced with difficulties, we find ways to get around them, using our own abilities and those of others, and by using things we have and the things we don’t. There is risk in that and that's why there is business. Now let's add nuance to the earlier statement that the simplest service is a joint venture between someone assuming risk and someone avoiding it. Let's replace the word, avoiding, with providing. Customers are providing risks that 'service providers' are gladly accepting. That inversion of logic is helpful in not only understanding why services truly exist but also why more and more things are being offered as-a-service, including cases in which nobody asks for it.

"Cannot, will not, do everything"

The propensity for services exists when people are unable to do certain tasks without stress, error, or waste. If someone is not lacking in skills or experience they may not have special tools, materials, or a conducive workspace. Things that are rarely used and expensive. Or, they may simply lack license and permission to perform tasks that are regulated because of the chances of personal injury or property damage. Thus, we have services that clean chimneys, cut hair, repair electrical circuits, bake wedding cakes, unblock arteries, block cyberattacks, and draft legal agreements. In yet other cases rules and regulations deny the do-it-yourself option because of the element of trust. Even the most capable, licensed, and experienced professionals have to rely on trusted third parties for things such as financial audits, psychiatric evaluations, and background checks for security clearances.

"Other things to do"

As people attach higher values to their time, they delegate more kinds of tasks, such as housekeeping, valet parking, and grocery shopping. Deciding to take the train instead of driving, allows a person to get some rest or get some work done. Parents pay for childcare when they can't be with their children for whatever reason. Apps, maps, and algorithms are making it easier to find people on short notice to do simple or menial tasks. Thus, we have seen growth in the gig economy. Outsourcing is not new to organisations. Airports, for example, outsource the cleaning of facilities and passenger screening. Airlines outsource catering and baggage handling. Contract research organisations conduct important parts of clinical trials on behalf of sponsors. Critical parts and sub-assemblies are subcontracted by aircraft companies. Even NASA now relies on Boeing and SpaceX for transport services, focussing its budget on core missions.

"Things we have, things we don't"

We cannot own everything. We do not want to. We have the propensity for services because of the things we have and the things we don’t. For our buildings, vehicles, and equipment, we pay for energy, maintenance, and insurance. But we could also lease and rent those things instead of owning them. We can borrow everything, from aircraft and shipping containers to soil aerators and professional-grade AV equipment. For the money we have, we use services that make it available to us everywhere through debit cards. For the money we don’t have, there are credit cards. Thus, some services make the things we have more useful and valuable. Other services make things we don't have available to us within windows of opportunity i.e. when and where we need them the most.

"Asset leverage"

The propensity for services exists because people want to get the most out of things. Both, the things we own and the things we don't. Banks lend your money and pay you interest. Uber and Airbnb started out with helping owners of homes and vehicles get more out of their idle capacities. Whether we own a vehicle, lease it, or rent it, we pay for services that provide fuel, parking, and passage through a tollway. Even before they put keys in your hands, some car rental companies put fear in your mind, urging you to buy additional insurance. As more things enter our lives, we are even more in the markets for services. With new kinds of things, we depend on new kinds of services. We have services that make digital assets useful and useable across devices, platforms, and other services. And since digital assets can be vulnerable to damage, loss, and theft, we have services to protect them. We also have services that verify, maintain, and protect our digital keys, cash, and ID.

"Artificial extensions"

Like bionic exoskeletons, services artificially extend our range. We can be anywhere on the planet, within a day. When we arrive there, strangers give us what we want, including permission to enter a country, local currency, and keys to cars and hotels. Not because they simply trust us, but because they trust the services behind our passports, visas, driver's licenses, credit cards and travel insurance. On a road trip, highways, fuelling stations, and payment networks allow us to go further and further. If we arrive at a vast expanse of water and there is no bridge, we can drive onto a ferry that will take us further. We can be at different places at the same time, making our presence felt elsewhere through video calls. Our ancestors would be surprised to see how easily we do what was impossible for them. They'd see us make documents appear and disappear, sending and receiving them in seconds; from thousands of miles away. Waving a card in front of a device seems to pay for stuff. They don't see notes or coins exchanged.

"Always be closing"

The more services extend our range, the more we overreach. We share more photos and videos than ever, using smartphones with ever increasing capacity in megapixels. But we never fall short of telecom bandwidth or storage, because there is always a service closing the gap. So we create even more content and share it even more with everyone, everywhere. Not just that. We come up with new ways of creating content, such as generative AI, which is very compute intensive, requiring a lot of electricity and processing power. But cloud computing will somehow close the gap, using nuclear power plants if necessary. Businesses routinely make plans knowing there will be shortfalls in resources. They still go ahead because services close the gaps with leases, loans, and lines of credit, college graduates, and flexible terms on office space. Those services in turn depend on other services to close their gaps and reduce operational risks. We have high schools for colleges, construction companies for commercial real estate, and reinsurance for insurance. Services are always closing the gap between possibilities and impossibilities.

3 Scale and spread

Bus and train schedules are betting on enough people in a population deciding not to walk or drive. Airlines are audacious enough to think enough of those people won't (or can't) take the bus or train. Hotels are betting on enough of them not having a place to stay. Restaurants stock up daily with perishable items, betting that, on any given day, enough people in a population, including visitors, will not cook meals or go hungry. VISA and Mastercard bet on enough of those meals not being paid with notes and coins. We can infect human populations with new ideas of not doing or not having. Take Swapfiets, for example; a bike rental service. It was audacious enough to offer bicycles on monthly subscriptions in the Netherlands – a country already with more bicycles than people. But it paid off. Enough people got infected with the idea.

"Propensity meets audacity"

On the other end of the spectrum, years ago Planet.com has a large constellation of small satellites in orbit covering the entire landmass of Earth, betting that, at any given moment, someone, somewhere in the world, would need high-quality images of an area of interest. Propensity meets audacity and more organisations incorporate satellite imagery into their work. Thus buyers and sellers prompt each other with more encouraging promises of demand and supply, getting better over time at making and keeping such promises. Instead of owning and maintaining costly stocks of parts and materials, airlines can pay Airbus a fixed amount per flight hour for a material and maintenance package that guarantees availability and response for aircraft on-time performance. Airbus spreads the costs across several airlines that subscribe to the idea, using mathematical models to pool risks like insurance companies do.

"Lower transaction costs"

Digital technologies have made it easier for demand and supply to meet within smaller windows of opportunity. Customers can more quickly and conveniently find things on short notice, locate, and unlock them. Providers can easily identify customers, allocate capacity, track usage, recover assets, and process payments. For example, in many cities, it is easy to find a car nearby, use it for a couple of hours, park it, lock it, and walk away. Cloud computing services like Amazon AWS and Microsoft Azure offer IT infrastructures upon which businesses can deploy their software applications for a few minutes, hours or days. Customers pay only for the time and resources they actually use – like how we once paid for phone calls and how we pay for electricity and gas.

"Too small to notice"

Hundreds of services run in the background when we are shopping online, or when browsing through the Netflix to watch a movie on our 4K UHD screens. Called microservices, they quickly do the grunt work while the macro has our attention. Some are always on while others are active in short bursts and then they’re gone. Many interact with each other, passing data, performing tasks, and displaying results. Billions of social network profiles receive instant updates as and when the socialising happens; each profile is uniquely rendered with ads, content and notifications. Another example is, how the stock price of a publicly traded firm updates right in front of your eyes, as you’re reading the story that mentions it. If you click on it, a chart pops up and shows how the stock is currently trading on the exchange. Microservices may be "too small to notice", but, operationally, they are in fact large in scale, serving hundreds of millions of users at the same time. In terms of emissions, that's a lot of microbial carbon.

"Too big to fail"

In 2008 the United States government bailed out banks with the $700 billion Troubled Assets Relief Program (TARP), fearing they were too big to fail. Nobody knew if those fears were unfounded and nobody wanted to find out. But imagine if the VISA payment network were unable to process card transactions for even a few hours. With over 65000 messages per second, a lot of pain would be felt everywhere. About 25 million flights will depend on air traffic control in the first 9 months of 2024; about 100,000 a day through several airspaces. Services supplying electricity, water, and gas are part of the critical infrastructures within the scope of national security. The definition of failure gets tricky in some cases. Services such as Facebook, Google, and X have been criticised for the misuse of user data and misinformation, but they haven't failed to create value for their customers because advertising is their actual business. For years the UK National Health Service has been criticised because of long waiting times for non-urgent care while being chronically under-funded. But it has continued to provide care for its patients every single hour, every single day. So has it really failed?

“When you want to know how things really work, study them when they're coming apart.” ― William Gibson, Zero History (2010).

4 Stress and strain

In our efforts to make things more sustainable, we should not forget the reasons why services fail or fall short of expectations. Services are contracts that encourage demand and supply to show up as promised within windows of opportunity – rectangles of time and space within which performances and affordances can happen. Both sides must do their part to fully enjoy the benefits. Each must make it easy and less expensive for the other to keep its promise. Without such mutual understanding, cooperation, and trust, the outcomes and experiences we desire will not materialise as expected.

"Unnecessary costs"

The problem is when the actual value of a promise turns out to be less than its 'face value' because of hidden or unknown costs. In view of that, the counter-promise in future, is risk-adjusted to match the lower expected value. That in turn prompts similar adjustments on the first side. Gaming mentality takes over, and, before they know it, the two sides quietly become more careful and distrustful of each other. Through passive-aggressive terms and conditions, they impose unnecessary costs on each other. For example, in a contract for the maintenance and repair of a fleet of trucks, the customer may ask for guarantees on the supply of spare parts and materials, such as, where the stocks are kept, minimum inventory levels, and a maximum markup on costs. The service provider may have no choice but to comply with those requirements and, either bake the additional costs into a base price, or move them elsewhere in the design of the service. Either way, the service as a whole becomes a costlier system. Neither side actually benefits from such unnecessary costs. But both sides feel safe. Contracts and services that are bloated with such costs, have lesser room for the additional costs of sustainability. This is true not only of a €240 million maintenance contract, but also the €2400 health insurance, the €240 airline ticket, and the €24 restaurant dinner.

"Nothing personal"

We can say "it's nothing personal", but there is lesser room for discussion about sharing the costs of sustainability, when there are 'unintended conflicts' between customers and service providers. Low levels of transparency and trust are one reason why relationships don't develop further. Or, why in reality services are not joint ventures but arms-length transactions. But why are promises less than their face values, apart from the usual uncertainties of the world that are already factored in? When the actual cost of providing a service turns to be much higher than expected, businesses seek ways to protect margins. But they cannot always simply raise prices because of competition and regulation. Take commercial aviation, for example. For a while now, airlines have been forced to advertise cheaper and cheaper fares to appear higher up on price comparison sites. We also have the common scenario of two flights on the same day, between the same two airports, but with a major price difference. Furthermore, pricing and revenue optimisation systems create several classes of fares for each flight. Each comes with its own set of conveniences and inconveniences; flexibilities and restrictions.

"Financial stress"

But airlines don't have a choice. It's getting harder and harder to cut operational costs. Like many other businesses that have borrowed just-in-time concepts from lean manufacturing, airlines are running tighter than ever before while also being heavily outsourced. They must try and get the most out of routes, schedules, landing rights, time slots, gate fees, fleet, fuel and crew. And understandably so. According to IATA, the airline industry expects net profits of 3.1% in 2024, compared to 3.0% in 2023. If that seems like a lot, for the 12 months ending June 30, 2024, the net profit of Booking.com was about 22%. Some airlines make more from their frequent flier programs than from flying planes. Large scale operations that perform well (whether of airlines or hospitals), have the capacity to absorb errors, exceptions, and variations, because they maintain "idle assets". But such capacity is too costly to maintain without healthy profits. Financial stress can thus lead to faultier operations.

"Faultier operations"

According to the US Department of Transportation, in 2023, 76% of delays and cancellations were not weather-related, but due to circumstances within the airline's control, including instances of a previous flight with the same aircraft arriving late, causing the next flight to depart late. It is not uncommon for a flight arriving at the destination very late, around the same time as a much cheaper flight. The promise turns out to be less than the face value. The airline may profusely apologise but does not compensate passengers for the delay unless government regulations force them to. Some passengers may shrug it off, others may be annoyed, but those who paid a lot more than the cheaper flight just to arrive sooner, would be quite upset. Such experiences not only corrode value but also erode trust. The lowering of expectations has financial consequences: the value of future promises based on time slots, is discounted. If the promise of an airline is simply transporting a passenger "from A to B", then shouldn't all flights from Atlanta to Boston cost the same?

5 Goodwill and trust

According to research at the University of Oxford, businesses could be liable for trillions in damages from climate lawsuits. New rules and regulations are making it difficult to ignore things that appear on double materiality assessments. But businesses will struggle to meet their climate goals without the cooperation and support of customers and suppliers. Or worse, with unresolved and unintended conflicts with those who promise demand and supply. Organisations can use their artificially maintained or monopolistic positions to insert costs into their service contracts. But the relationships won't last very long, because, sooner or later, competition and regulation can intervene and weaken those positions. Whereas, the goodwill and trust of customers and suppliers, across daisy chains of demand and supply, can help a business strengthen its positions. And also, the enterprise would be more successful in securing new commitments and considerations that may be necessary to align with new realities in a market.

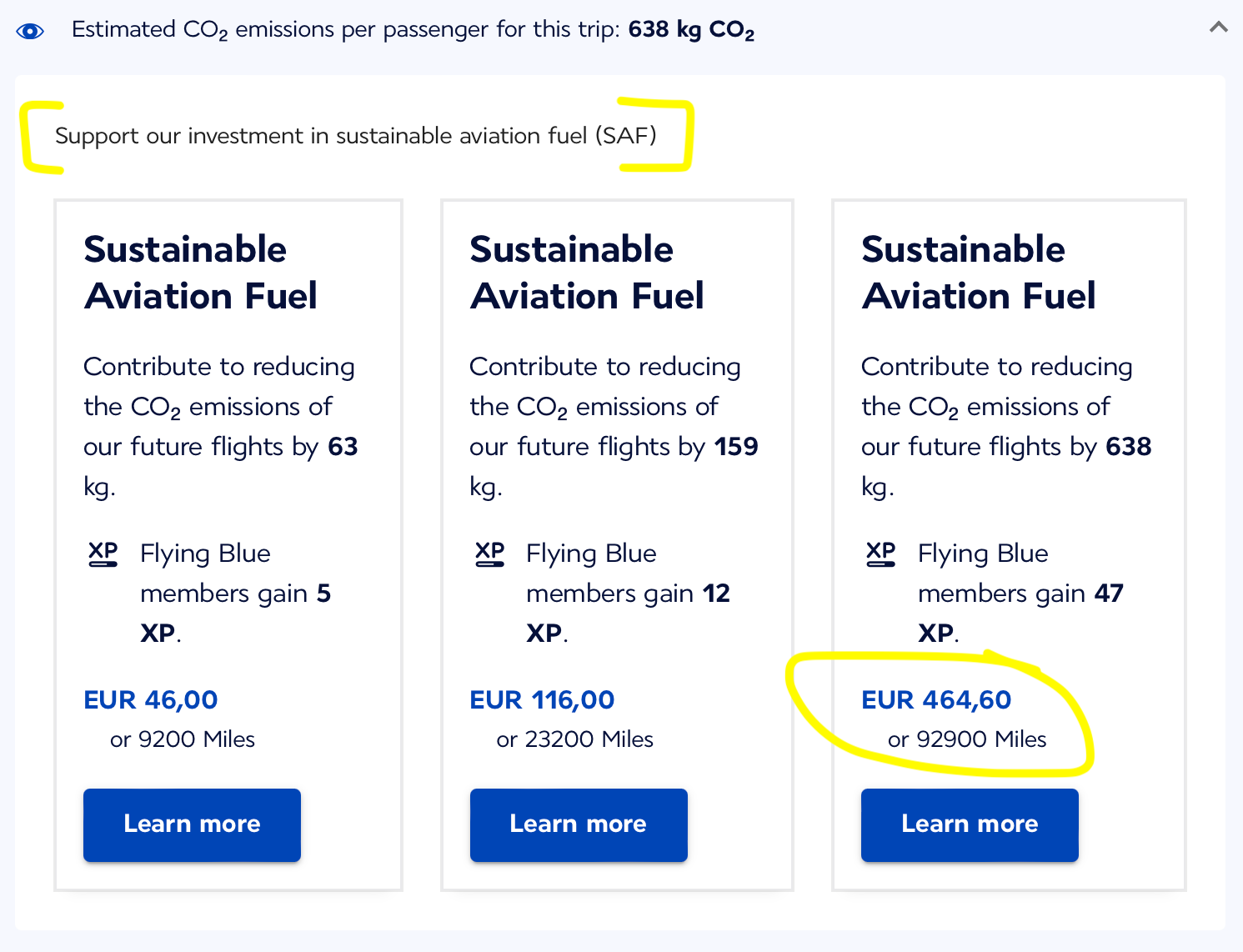

"Paying it forward"

Let's take sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) to illustrate the value of stronger relationships between customers and suppliers, based on high levels of goodwill and trust. European regulations require that, by 2025, at least 2% of the fuel available at all EU airports has to be SAF – 6% by 2030, 20% by 2035, and 70% in 2050. Airlines wish to invest in it but SAF is still too scarce and expensive compared to kerosene. Some airlines are asking passengers to pay it forward and support their SAF investments and hoping that many will oblige and participate.

Cost-conscious customers want cheaper flights. But even climate-conscious passengers might balk at paying for the extra SAF option if there isn't enough goodwill and trust toward the airline, and the industry in general. They would anyway hesitate when they read the disclaimer attached to the option:

To be used, SAF is blended with kerosene and stored in the airport fuel supply systems to refuel all aircraft. Although we cannot guarantee the presence of SAF purchased via the Extra SAF fare specifically on your flight, the benefit to the climate remains the same.

"Questions pop up"

Here, the airline is bringing the issue of sustainability into a ticket purchase and making sure the 638 kg of CO2 weigh into personal decisions to live more sustainably. But it cannot guarantee the presence of SAF in the flight the passenger will be actually on. Instead, the airline is asking its customers to pay it forward i.e. contribute towards reducing the CO2 emissions of future flights. In general, a lack of goodwill and trust creates uncertainty and doubt. Questions pop up. What about the extra money from the previous flyers? Didn't they buy SAF for my flight? Should we pay more to be flown on a fuel-efficient Airbus 320neo with LEAP-1A engines burning SAF, because of lower emissions? Or should we pay less because of the lower operating costs? The bigger question is, for the Extra SAF option to sell well, is there enough solidarity toward fellow passengers, let alone toward future travellers? Aircraft cabins are pressurised and pricing policies have made them contentious. Overhead bins are fought for and even the reclining of a seat may lead to arguments.

"Cross subsidies"

Before cheap fares, airlines gave passengers a baggage allowance as part of every purchase. Looking back at it now, through those full fare purchases, passengers were actually paying it forward. If Peter did not check any bags but Paul did, it didn’t matter. They both contributed the same fixed amount toward the total cost of whatever goes into the cargo hold. It is based on the understanding that next time it could be Peter, not Paul. Frequent fliers 'paid it forward' for their future travels. Down the aisle, Alice and Bob, on vacation with small children, are quietly thankful to everyone else traveling light. The airline is quietly thankful children weigh less. Passengers or bags, the aircraft engines cannot tell the difference. On some flights the airline bears too much of the remaining cost burden, on other flights, not a lot. Full fares provided an enough of a cost buffer and the cost variances cancelled each other out across schedule and route.

"Basic economy"

But then, the industry went from one crisis to another since 9/11. To get through the turbulence in the wake of the 2008 crisis, airlines started charging for bags. The strategy worked so well they extended the price discrimination to seating and boarding. Aircraft seating maps are like real estate in Manhattan – a grid of individually priced addresses. How much you pay depends on how far you are willing to sit from prime locations. Even exit row seats are sold to the highest bidders, instead of being reserved for those who are willing and able to help in case of an emergency. How that policy does not contravene safety regulations, only lawyers can explain. If you think about it, the basic economy fare buys merely the privilege to enter a security checkpoint and arrive at a boarding gate, and then, aboard the aircraft, the ticket guarantees a seat belt. Everything else is priced as an option. Passengers can use their air miles to pay for options, but loyalty points do not have the purchasing power they did before. Too many points, chasing the same few privileges, have caused inflation.

6 Balance and distribution

There seems to be evidence behind claims that happier cows make better milk and cheese; or why you should pay more for organic. Whether we can make similar claims or not, in our efforts to make services more sustainable, we shouldn't forget why they make us happy. Services make life comfortable, safe, and secure, and are there when we need them. Some we don't even realise they're there until they fail. On the other end of the emotional spectrum, services create excitement by making possible the impossible, extending our range, and closing the gaps between what we have and what we need, and between what we can and cannot. In return, we willingly pay for them, including taxes for services provided by governments. Services are voluntary by nature, on both sides of the demand-supply equation. Therefore, when loading them with sustainability costs, we have to keep in mind the balance and distribution across a set of promises.

"Hierarchy of concerns"

Not all promises have the same load bearing capacity. There is a hierarchy of concerns: core, essential, societal, and optional. Core promises establish the basis for valuing and pricing the other three types. In the case of the airline ticket, transport between two specific time slots is the core promise. Seats with belts are essential to the core. Some type of safe and secure boarding is also essential. The screening of passengers and bags is societal i.e. we as a society insist upon it through the policies our governments. We pay for screening not because we believe we could be a threat, but possibly everybody else. In-flight meals and entertainment are optional. As is the room to lie down or stretch legs on business class beds. Taxes and fees cover other essential and societal items that make the airport environment safe and comfortable.

"Sensibility analysis"

Sensitivity analysis is key to pricing decisions. But it should not be applied before a sensibility analysis. In general, core and essential items should be not be unbundled and separately charged. Imagine an Italian restaurant serving pasta but charging extra for the sauce. Carrying bags has been essential to the human experience ever since travelling has been a concept. That’s why baggage fees have had negligible impacts on how much people continue to carry. Airlines are happy with the additional revenue and profit, but passengers are not. Making baggage optional and charging for it, creates silent resentment. From the passenger perspective, SAF or not, the fuel is part of the core promise. It's essential only from the airline's perspective. Thus, asking passengers to make a goodwill contribution towards 'possible SAF in future flights' and at the same time charging more than ever for bags, is likely to evoke a negative response. Passengers, of course, must understand that aviation fuel is expensive, and engines burn it for every kilogram of weight. They should stop expecting even cheaper fares and consider the time when the price included a cross-subsidised baggage allowance, whether they check bags or not.

"This, is like that"

Maybe airline pricing will never go back to what it was. Southwest Airlines is the only remaining major carrier that does not charge for checked bags. Airline pricing is merely an example, but it is instructive of the kind of challenges other industries may also face in making a service more sustainable. In each industry, teams dedicated to finding sensible solutions, will of course explore the use of new technologies and materials to help reduce carbon intensities. What would be the “320neo” for commercial laundries serving hospitals and hotels? Or the “LEAP-1A” for sewage treatment plants. What will be the “SAF” for generative AI, the newest industry of all? Through analogy and abstraction, they will find new and interesting answers from other domains. But they must also extend their inquiry to the more relational aspects of an operation, with respect to customers and suppliers, by asking what the "baggage handling problem" could be in their industry; "seating and boarding", "screening" or "overbooking". In doing so, they will discover the true extent of the support they have from customers and suppliers, for their sustainability programmes.

"Colour of carbon"

But what works in one service may not work in another. Take urban waste collection, for example. In the hierarchy of concerns, empty bins are part of the core promise; removal and transportation of waste are essential to that core. Providing several, separate bins for different kinds of waste is optional, because of technologies that facilitate separation at a later stage. Recovering energy and materials from the waste is societal. A society may insist on it through incentives for local industry and government regulations. A landfill is not optional. Not until the local circular economy crosses thresholds. Now, if we could measure the amount of waste households deposit into neighbourhood bins, should a municipality charge its residents for excess waste as airlines for excess baggage? And if so, what would be our justification apart from saying it is good for the Planet? This is when the colour of carbon matters i.e. what the underlying promises are. Would a majority of residents be more willing to pay more every month? And if so, how much if it would be in return having more "emptiness" because of bigger bins and more frequent collection? How much of it toward greener transportation? Would a majority simply vote down the idea in a referendum, or worse, vote out a government?

Conclusion

The tragedy of commons aside, at some level or other people accept fair and equitable distributions of cost and risks. Many, to some extent or the other, are also willing to contribute to a greater cause, or at least pay more for something without expecting immediate and direct benefits. So how can we get them to pay it forward? How can we get them to knowingly subsidise each other? How do we get everybody to offer a little so nobody has to offer a lot? How do we get everybody to suffer a little so nobody has to suffer a lot? Those are the key questions for any approach to mutualising risks. There are useful ideas from insurance. But also, several large urban transit systems charge a fixed amount per journey, instead of charging for the actual distance travelled. Not all passengers will travel the full distance, thus costing the system less and subsidising those who travel farther. Someone who travels two stops today may travel ten the next time, and vice versa. Framing is everything.

Profitability should not be, and need not be, in conflict with sustainability. A financially healthy business is more likely to survive the stress and strain of transitions toward more sustainable futures. The same is true of local and national governments not facing budget deficits. Costs are facts, pricing is policy. There is wrong nothing with super-segmenting a population and applying price discrimination, or taxing them more. But in the process, we must be careful not to lose goodwill and trust, or worse, create resentment. Recent elections in several European countries have shown, that feelings of resentment can build up in a society as a whole and cause indiscriminate pushback against all policies designed to slow down climate change. That's not going to help as we get further into the sustainability challenge i.e. when everybody is feeling the pressure, customers and suppliers start implicating each other in double materiality assessments, and consumers and taxpayers are not willing to accept any further costs that get ultimately passed on to them.

How much more sustainable an industry can be while still being profitable, really depends on the nature of the underlying promises and the hierarchy of concerns. That is why, as part of their materiality assessments, organisations should conduct design audits that reexamine the fundamentals i.e. why a service is a service in the first place from both perspectives – the organisation as a customer, and as a service provider. Such exercises will help clarify whether a promise is actually core, or essential. If neither of those, then whether it is societal, or optional. Such clarifications will then help in setting up more meaningful discussions with customers and suppliers, about mutualising costs and risks. The results may vary from one industry to another; every industry having had its own recent history, going back the past 25 years. Nevertheless, going forward, organisations can make faster progress toward their climate goals by sensibly avoiding unintended conflicts with customers and suppliers.