This essay shows how services are soft infrastructures of societies, through the fictional journey of a traveller going from the Netherlands to the United States. Services fade in and fade out, frame to frame. Some services are in the foreground while others remain in the background.

Alice is on the InterCity train from Utrecht to the Amsterdam Schiphol airport, seated in a first-class compartment. She is listening to music, sipping coffee, and reading news. The music is from the Daily Mix made for her by Spotify. It includes her favourites and suggestions from a recommendation algorithm. It is an endless mix. More songs load as she listens. As the train crosses the Amsterdam-Rijn canal, she gets notifications on her smartphone. Before she has time to look, she is politely interrupted by the train conductor. She hands over her OV chipkaart, an NFC card loaded with the ticket for her journey. It can be used across all modes of public transport in the Netherlands, including bicycles for rent. The conductor holds the card to a hand-held terminal to see whether Alice has checked in at the station before boarding the train, as all passengers are required to do, and if she has loaded the first-class option. Alice is using the business version of the card that employers provide for work-related travel, allowing for the charges to be paid by a corporate account. Time to take a look at those notifications.

She has received a few »likes« on the tweet she posted that morning. Another notification is from Dropbox, a digital service that facilitates collaboration among team members through the sharing of files and folders. Every time a user creates or modifies a file in a shared folder, the service instantly synchronises all copies and informs everyone. Most crucially, it provides unlimited cloud storage and users can access files from any device connected to the Internet. Alice opens one of those files, makes a few changes, and adds a comment. As she closes the document, a software agent that's always running in the background, goes to work like a dutiful team assistant and does all the clerical work to keep things tidy, and everyone on the same page. Next, she opens a browser to Planet.com to look at the map of an area Alice and her team are keeping an eye on. She marks the area of interest for which she wants a satellite image. By the time she joins her team in Washington D.C. the next afternoon, a satellite will have scanned the area and sent it for processing.

Alice and team can then see the changes that have occurred since the time she left Utrecht. They will have access to high-resolution, colour-corrected images with accentuated detail. Analytical software uses machine learning and computer vision to transform raw images into layers of insight. Like experienced analysts at intelligence agencies, the system detects and classifies things such as buildings, roads, vehicles, rivers and mountains. Placed on top of a historical stack of hundreds of previous images, the latest capture will add a new layer of insight. Alice is interested in monitor changes for the purposes of planning disaster recovery and relief. The train arrives at Schiphol. The station is right underneath the airport, making the transit easy for travellers, especially for those with children and heavy luggage. As passengers step onto the platform, they exit one smoothly running system and enter another.

They step onto a moving walkway and soon emerge into the cavernous main hall of the airport and into a whole different ecosystem of services. A large digital board displaying departures, advises travellers which check-in desk and gate to proceed to. Nearby is another board displaying the train schedule, for the benefit of those who have just flown into Amsterdam. With all those people coming and going, this area can get quite crowded. There is always someone hurrying to go one level up to the departure halls. But even they won't fail to notice officers of the Koninklijke Marechaussee, a military force that is in charge of airport security and border control. A nexus of industry and government, facilitates the flow of passengers. Several agencies collaborate to make things smooth, while maintaining safety and security for all.

It is time for Alice to check in. She is flying non-stop with KLM. She has a baggage allowance as part of her ticket purchase. She has one bag that is too large for the overhead cabin and contains items restricted to the aircraft’s hold. She approaches the area where bags are to be dropped off and gets ushered towards the end of a long line of economy class passengers. Alice has always proudly been a pleb. She doesn't mind. But the line moves fairly fast and Alice soon finds out why. There is a long bank of robotic machines that look like they're from a Star Wars movie. The machines are capable of dialogue and interaction with passengers and bags. They can do everything a human agent can do: check IDs, confirm passengers details, ask questions about restricted items, check weight, refuse to accept anything over the 23 kg limit, issue tags, take custody of bags on behalf of the airline and place them on the conveyor belt right behind. Alice is impressed.

Baggage handling is a series of performances: identifying, linking, weighing, screening, sorting, holding, loading, transporting, unloading, retrieving, and returning. The bag tag with barcode, plays an important role throughout the system, from check-in to baggage claim at the final destination. The airline’s departure control system generates a 10-digit numeric code that link bags to the passenger name record. The international standard that airports and airlines follow, calls it the license plate number, because it has all the information baggage handling systems need, to route a bag through airports and airlines. That includes, which flights the bag should be loaded on, who the bag belongs to, and which airline issued the tag. But most importantly for Alice, the tag the robot has just printed, which she then attaches to her personal property, makes the bag ready for screening, after which it can proceed toward the aircraft.

Baggage handling is also a series of affordances. To start with, there is the bag tag, the conveyance, the tray with RFID chip, the security clearance and the safe passage through a secure channel. An underground system of highways connects the landside of the airport to the airside. After the security check, near Lounge 2, there is a section of the floor that is a glass ceiling. Through it you can see the bags quickly pass by. Chances are you might spot your bag making that underground journey. There are a few more affordances ahead. Once the bags have been sorted, they are afforded space on pallets on which they remain until they are ready to be loaded into the hold of the aircraft, the greatest affordance of all. A performance involves one thing acting upon another thing, such a conveyor belt dragging forward a bag, by friction. An affordance involves one thing being available to another thing, such as space on the belt.

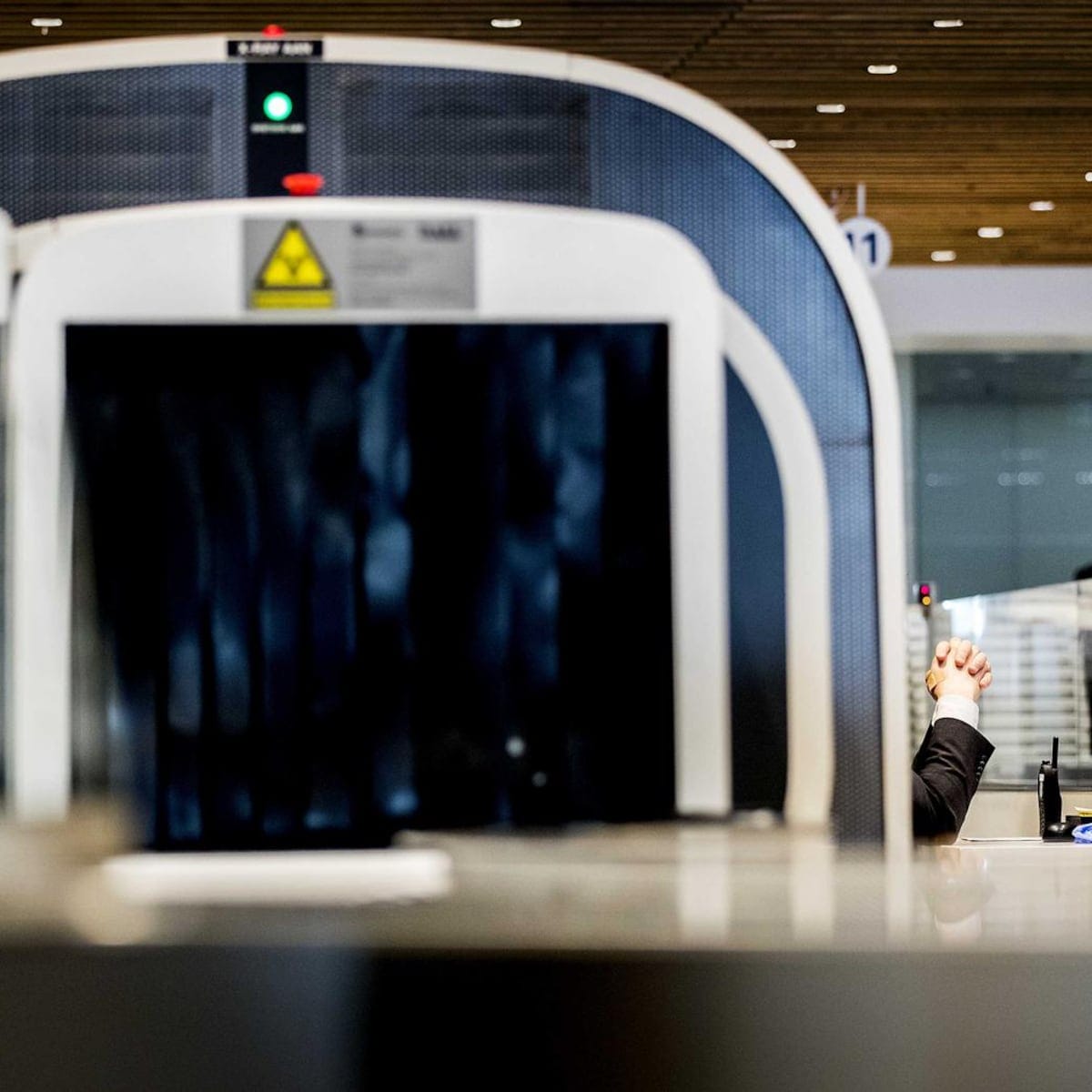

There are many other performances and affordances to go. While her checked bag is being taken care of, Alice and her cabin luggage go through a security channel. There are two separate scanners in each channel – one for property, the other for person. The activity of screening, is the performance. The permission to proceed, is the affordance. Performances and affordances go hand in hand. Or, actually, more like: left foot forward, right foot forward, left foot, right foot, right foot, left foot, left, right, left right, right left, left, right. Till the sequence comes to an end. Once you see this pattern in services, you really can't unsee it. You can cover an entire ecosystem of services, step by step, block by block, by marking the affordances and performances, or Xs and Ys.

Since Alice is travelling to the United States, she has to leave the Schengen area by crossing a border, which, in this situation, is an imaginary line dividing a section of the airport. Her United States passport, embedded with a biometric chip, affords her the privilege of using the self-service passport control gates. The authority of a state is vested in the apparatus that includes a document scanner, a camera and an electromechanical glass barrier. An armed officer supervises the control procedure and handles errors and exceptions. The verifying of her identity, is the performance (Y). The permission to cross (evident in the opening of the gate), is the affordance (X). Another performance-affordance pair define another step in her journey. Once she exits the gate, she has technically left the Netherlands without actually leaving it yet.

After crossing the border, Alice glances at the time. She has about an hour before the boarding commences at gate D2, which isn't too far away. She isn't keen on eating, drinking or shopping, so she decides to spend some time relaxing in the Lounge 2 area. Airports have evolved a lot. The bare minimum of an airport is an airfield and runway for aircraft to take-off and land, attached to a building from which passengers can board a flight or disembark. That's the skeletal requirement. But of course, airports today are massive complexes hosting hundreds of flights per day and thousands of passengers. In fact, with hotels, restaurants and shops, they are small but busy towns with transient populations. There is always someone rushing out of security directly to the gate, trying not to miss their flight. Most passengers though are likely to wait for a while. The architectural designs of airports are mindful of that.

Passengers stow away their bags in overhead bins, place personal items in seat pockets, and settle down in their assigned seats. Meanwhile, ground services fuel the aircraft, stock it with supplies, load it with bags, inspect it, and prepare it for the next take-off and landing cycle. Soon the pilots will get permission for pushback, be given a runway assignment, and take-off clearance. The control tower coordinates the movement of aircraft, separating them from other traffic and giving each temporary access to a most valuable resource – the crisscross of runways built on a reclaimed piece of land in North Holland, bought from a farmer in 1916 for 55229,40 guilders.

After take-off, other services come into play, on the ground and in the air. The core service of course, is the air transport. During the 8 hour flight to Washington D.C., for the passengers and bags, the Airbus 330-300 aircraft is, both, a capability and a resource. From the capability, comes the performance: carrying the loads while moving at ~900 km/h, at an altitude of ~10 km. From the resource, comes the affordance: seats in a pressurised cabin and the space in the overhead bins and underneath hold. Airlines measure their capacities in available seat-kilometres, or ASK. That is, one seat travelling a distance of one kilometre equals one ASK. If you look closely, that metric reflects the affordance-performance promise of any transport service. KLM has configured the 268-seat Airbus cabin with 18 business class, 36 economy plus, and 214 economy class seats. KL 651 will travel a total distance of 6214 km. That makes the total capacity of the flight, 268 x 6214 = 1,665,352 ASK. Applying the KLM average of € 0.0771 per ASK, and if all the seats are sold, the expected value of revenues is €133,228.

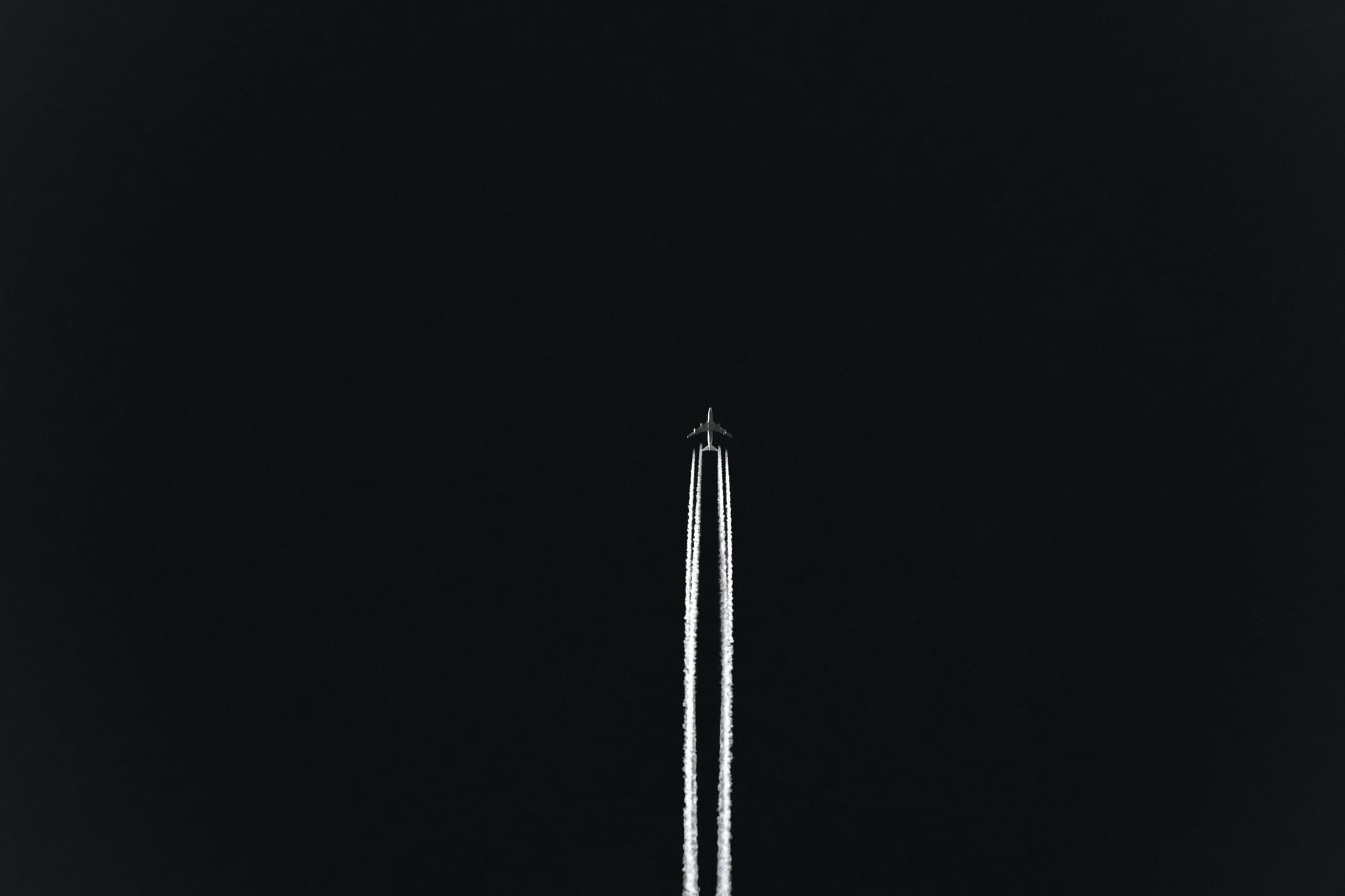

Controlled airspace through which commercial flights travel, is divided into flight information regions, or FIR. Each region is under the management of an air traffic control centre. The controllers are aware of all the flight plans and their job is to maintain sufficient separation between all the aircraft in their region at all times. The next time you see vapour trails high in the sky, you can imagine the aircraft flying through its own private tunnel. The invisible tube continuously materialises 5 km in front of the nose and dematerialises 5 km behind the tail, disappearing into thin air. It's invisible infrastructure, as NATS calls it. Each country controls its own airspace and charges the airlines overflight fees. The fees include the use of air traffic control and other navigation services. It could be a fixed fee per crossing, or a variable amount based on the aircraft type and distance traversed across the national airspace.

As KL 651 completes its descent and glides into approach, the wide-body aircraft, carrying 245 passengers, has been cleared to land on runway 19R. It will then taxi to a terminal gate at terminal C of the Washington Dulles Airport. There, people and things patiently wait. Marshalers, chokes, jet ways, pallets, unit load devices, bag loaders, wheelchairs, gate agents and other ground staff, all wait for the pilot to cut off the engines. Passengers flying to Amsterdam start getting up from their seats to line up for the boarding.

Services are arrangements and agreements – agreements between people and arrangements between things. The arrangements, i.e. two things put in position to make contact or connection, are necessary for performances and affordances »to happen.« For example, a bag has to come in contact with a conveyor belt, to be carried. The agreements are necessary for the arrangements »to take place.« The passenger has to agree to handover the bag to the airline before it can go on the belt. As we have seen throughout Alice's journey, several arrangements and agreements were necessary. Some of them are more in the foreground and others in the background. How good the arrangements are, influences the quality of the performances and affordances and therefore the quality of outcomes and experiences.

During the 30-minute train ride, the train was part of three major arrangements: one with the tracks underneath, one with the electricity cables overhead, and one with a track-side telecom network. The arrangements were in place because of the agreements between NS, the train operator, and Pro-Rail for the tracks, Eneco for the electricity, and Nomad Digital for the WiFi bandwidth. The last one is the least obvious. By integrating cellular networks, trackside Wi-MAX networks, and a wireless client bridge, Nomad sets up a single and continuous broadband connection, for passengers to have WiFi throughout their journey.

Just before boarding the train, Alice placed her OV-chipkaart in close proximity to the card reader on one of the many gates and posts. That brief gesture was enough to load her train card with a valid fare. With the fare, came WiFi privilege. A dialog box pops up when you try to join the train’s WiFi network, presenting the terms and conditions for proper use. Accepting that agreement allows Alice’s phone and the train's WiFi routers to form a connection to the Internet. Alice can now treat that connection as a temporary asset and give it to services running on her phone and laptop, including Spotify, iMessage, Dropbox, and WeTransfer.

The Spotify app arranges through the phone's operating system, for the hardware to produce sound so the daily mix can endlessly play. If a song on the mix isn’t already on the phone, the app connects to Spotify’s servers and receives more songs, making use of Alice’s temporary asset. Spotify’s licensing agreements with copyright owners allow that arrangement to take place. Similarly, Dropbox has Alice’s permission to use the connection to send and receive data, every time it detects changes to a file. Meanwhile, one of the 150 satellites that Planet Labs has orbiting around the Earth, is looming over the landmass within which Alice has marked an area of interest. Camera and coastline will come in contact with each other, for the rectilinear propagation of light.

Alice got some work during that ride to the airport. On one hand, there is nothing special about that. Thousands of such journeys happen every day. On some other occasion, Alice could have been chatting with her mother, scrolling Instagram, or simply looking out the window at windmills, cows, and canals. Maybe others on the train were doing such things while Alice was working. On the other hand, whoever is travelling and whatever they're doing while train is moving, there is in fact something special happening: there is a continuous band of services that becomes thicker or thinner but never breaks.

At the station, the platform, the tracks, the electricity cables, and the double-decker row of seats, form the initial band of services. Then the platform disappears from the band as the train leaves the station. But soon enough the WiFi connection is added and the band broadens. Then it becomes even broader as the files start transmitting and song tracks, playing. If mid-way through the journey, Alice decided to shut off all those digital services and simply look out the window, the band would have narrowed again. So you see, how the money Alice and others spend on a train ticket, or some other form of transportation, pays off with every metre of travel and at several different rates. That's what's special about the ecosystems of services our societies rely on.

This photo essay is based on a narrative that appears in Chapter 2 of my book, Thinking in Services. It has been edited with a few additional paragraphs, photographs, and hyperlinks.