If you must improve the design of a service, you must first look it with child-like curiosity and imagination. Then you see what that service is truly about and the elements of design that make it possible, including things that aren't that obvious. Having seen the service that way, you are less likely to make design decisions that compromise the core value. In this fictional narrative, of Khairun enjoying a day, we see extraordinary things in ordinary services such as grocery stores, medical imaging, parking, and elections.

11:35 Time to Ottolenghi

Khairun opens her favourite Ottolenghi book to a recipe she has never tried. It calls for quinoa. Khairun reaches into her kitchen shelf and there it is, waiting to be cooked. The recipe also requires some feta cheese. Khairun opens her fridge. Where is it? She rolls up her sleeves and extends her hand so it goes all the way to the back of the fridge. Not finding it there, she extends her hand through the fridge, into the kitchen wall, out of her home, into the neighbourhood. After a friendly wave to a neighbour, a Dr. Seuss fan, the hand travels two blocks, then into the local grocery store and all the way to the back to open the door of the "back-up" fridge. And there it is, the feta! Khairun grabs a small packet of feta and retracts her hands to bring the crucial ingredient to her kitchen counter. As her hand leaves the store, it makes two simple gestures: it gives the store money and data. The money rewards the agency that kept feta in that fridge knowing Khairun might need it. The data adds to the intelligence.

It’s not just Khairun’s habits. Others do the same, whenever they reach for something and it’s not there in the fridge or on the shelf. As a retail end of supply chains, the store ensures continuity in lifestyles and diets by predictively caching food. Everybody has access for a fee. The fee has two components. The ‘consider it your own’ component is for the privilege of reaching into the store and taking what you need as if it were your own. The ‘make it your own’ component is for you to carry on that pretence and carry things out of the store. Cache and carry. The shoppers are like a buyers’ cooperative. There is no minimum purchase requirement but everybody shares the cost of stocking the facility so that it almost always has what their long, snaky hands reach for. Their aggregated grabbing habits allow wholesale purchases on part of the store. Local cultures, cuisines, seasons, and trends predict what a hand might be grabbing next. Every purchase adds a data point. As a result, the probability of Khairun and others not finding what they need when they need it falls below a threshold.

Khairun and others could stock a lot more at home so their hands don’t get tired from all that expanding and contracting. However, there is only so much shelf space at home and, after a point, the carrying costs of kitchen inventory would be too high. There is another advantage. Many of the goods are perishable and have expiry dates, but are less likely to expire on the public shelf because someone or the other will run out of them. Fresher goods are in stock that way. There will still be some spoilage, but that cost is spread across the entire population. Over time the »elves behind the shelves« get better at making predictions from historical data. Google analyses emails, searches, and text messages, to display personalised ads. The store analyses past purchases to »display goods«. By understanding the propensities of a population, the store maintains the right assortment of goods within easy reach. For Khairun and friends, their own private stock on public shelves.

15:30 The hanging protocol

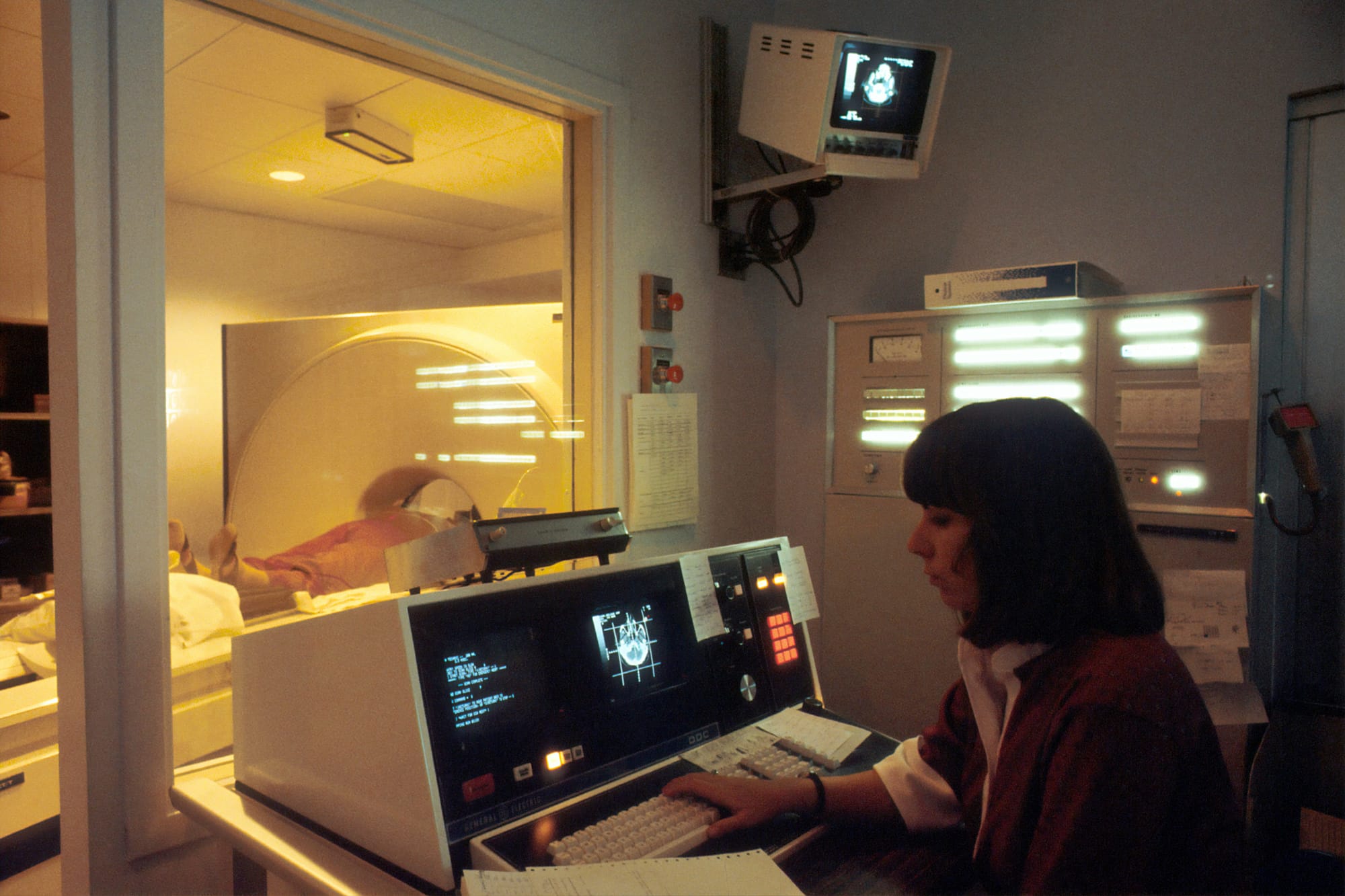

Later that afternoon, Khairun is sitting in a chair paying very close attention as she begins to grasp what’s on screen in front of her. She is thinking to herself: »The level of detail is astonishing!« She is listening to Dr. Langedijk as he points to a particular nerve on an MRI scan. It is the reason why she has sharp pain in her lower back. They go through several frames of anatomical detail displayed in extremely high resolution. The doctor can control the views: zoom-in, zoom-out and go from one frame to another. It’s like a storyboard someone has put together in time for their consultation. »It is called a hanging protocol,« the doctor explains, noticing the astonishment. It’s how the images and their various views are arranged, in a way that allows doctors to have a full and proper discussion about a health condition, with colleagues and the patient, to develop a treatment plan. The physiotherapist is in the room with Khairun.

We have come a long way from Röntgen’s X-rays to the 7-Tesla whole body MRI scanner and ultraportable ultrasound scanners that can be plugged into a smartphone. Continuous and preventive care requires teams across specialties to collaborate across points of care through electronic medical records, including images. Given their heavy workloads and the need to fully attend to patients, it is important for physicians to have quick and easy access to medical images and on any display device that is secure and private enough for protected health information. Picture archiving and communication systems (PACS) help make that possible. That is why Dr. Langedijk was able to quickly set up for Khairun's consultation immediately after the previous appointment.

The images were from the medical scan Khairun went through the previous week. She was dreading the procedure, but the radiography team carried it out so well, including the way they carefully placed antenna coils to capture the image. They showed a lot of care toward their patient, knowing how it feels lying inside a narrow tunnel and being subject to an intense magnetic field. The magnets make loud noises as they go on and off. Khairun was surprised to hear that, every now and then, technicians put themselves through a mock procedure, just to remind themselves of what it feels like for patients.

Khairun leaves the hospital quite satisfied with the treatment Dr. Langedijk and the team have proposed. She feels lucky to have such a fine doctor. And of course the technology behind it all. Being a geek, she is also wondering what the images from that 10.5-Tesla machine at the University of Minnesota would look like. The magnetic field in that one is 10 times greater than the standard. Right now though she needs to get to the polling station before it gets too late. She hasn’t missed voting in an election in the last 48 years. She is not going to start today.

16:15 Detachable time

There is a public parking lot next to the hospital. It is operated by the municipality. Khairun walks in that direction. She now has to drive to a polling station to cast a ballot. She hasn’t missed a chance to vote in an election in the last 48 years. She is not going to start today. She has to leave immediately to get there on time, before the polling closes. There are several unused minutes left on the parking meter but she is going to donate that time for the benefit of someone else.

Parking is a service she only sometimes uses because she has a bicycle and often takes the bus. But when she was working at the municipality, Khairun was part of the team that wrote new regulations for public parking. On one hand there was growing public opposition against vehicular traffic in favour of making streets friendlier to cyclists and pedestrians. On the other hand, there were enough residents who, for various reasons, preferred and needed to drive. They weren't happy about the shortage of parking space. They often had to drive around too long looking for parking spots, thus inadvertently adding to the traffic. Additionally, to discourage driving, the city had made parking more expensive per hour. It also raised the fines for parking violations. That policy caused a lot of consternation among drivers but also small businesses that benefit from the availability of public parking.

Parking services attach fixed blocks of time to the spaces they rent. The time is displayed on the parking meter attached to the space. When drivers vacate a space early, they give up the remaining time attached to the spot. The next vehicle pulling into that spot could use that time and top it up by paying for some more. Some systems print a receipt with an expiration date and time, to be prominently displayed on the dashboard of the vehicle. In theory, the same driver (or someone else) can use the remaining time on a separate occasion if that happens to be within the same time slot and zone or parking lot. That, of course, rarely happens. Yet other systems attach a license plate number to the receipt, thus restricting the use of the time to a particular vehicle. Enforcement staff can quickly verify on a handheld device that a vehicle has time and impose a fine if not.

Municipalities did not mind the additional revenues from parking fines. Local governments are not always flush with cash and there was always a project or programmes looking for additional funding. But Khairun saw an unintended conflict in relying on those revenues. It is one thing for the government as a public enterprise to bring in valuable revenues from the fair use of public property by everyone. Fines are there to discourage those who deliberately avoid paying. Not for punishing others with better intentions. Too many people were being fined when they were a just few minutes late getting back to their vehicles. The fine would have been the same if they hadn't paid at all. Data showed that, on average, people were roughly the same number of minutes late, as the unused time when they left early. But the city wasn't reimbursing that time, was it? That bothered Khairun and a few others.

She spearheaded a project to upgrade the mobile app drivers use to find and pay for municipality parking. If their vehicle is running out of time, drivers can add more time using the app, without having to get up from their flatbread or flat-white, or hurrying up on the grocery shopping. That helped avoid parking tickets with hefty fines. And if they returned to the their vehicles to leave early, they could use the parking app to either stop the meter running or donate the remaining time to a forgiveness fund. That way, when someone else was late, went past the time limit, or forgot to top up the time, the system would first allocate a limited amount of money from that goodwill reserve. The amounts were just enough to help many people avoid fines. Others still got fined, but knowing that society is willing to show some tolerance toward everyone.

17:37 The counting protocol

Khairun arrives at the polling station, feeling the same sense of excitement she felt when she voted for the first time. She gets just one vote, like everybody else. She believes, not only is every vote counted, every vote counts. Besides, she is about to use a service she has already paid for through taxes. Now she is going to get what she paid for: the ballot. She has seen the paper ballot evolve through all sizes and formats. Today though the ballot presents itself in digital form, through a simple and intuitive user interface that guides voters to their choices and quietly captures their opinion. As a MUJI fan, Khairun loves the design, for not only what’s been included but also for what’s been left out. To her, the capacitive glass surface is still that »beautiful piece of paper« only a government can print. As a retired civil servant, she knows something about that special colour of ink called public trust, that makes ordinary pieces of paper have legitimacy and authority. Pixels may have replaced pigment, but the personal opinions of citizens are still converted into votes. Votes that can still give governments a nasty paper cut they forget what they promised in the previous election.

It’s been a long day for Khairun, but she is happy as she heads home. Tomorrow she will go to the cinema to watch a new film, then to a bank to visit a locker she has not opened for years, and then a sauna.

This piece is based on an excerpt from my 2018 book, Thinking in Services.